Zahir, “Mind Your Step”

Whoever wrote that art is not progressive—that it doesn’t advance as artists learn how to better express themselves and pursue their goals—certainly didn’t look at the way the century of Surrealism has progressed. When, in 1924, André Breton published his Manifesto of Surrealism, he spoke to artists who sought ways to escape the rational mind’s control over the production of art, who wanted to allow the unconscious mind to speak for itself—something they were hard at work seeking to do. Some were waking themselves up at night in order to record their dreams while others were inventing random processes that depended on chance to defeat their instinctive imposition of order and reason on the creative process. Precisely a century later, the forty artists who responded to SLCC’s Gallery and Art Collections Specialist James Walton’s call for the Surrealism of today have absorbed the results of a century’s experiments and learned how to willfully free up their own unconscious impulses. The results, in two shows titled The Uncanny Traveler and Mystical Forest, will be on display until late September.

Two superb examples are ink drawings by Christian Degn: “Mountain Mind” and “Desert Immurement.” In the former, a desert landscape takes shape in a human skull. Of course, the mind should no longer inhabit a no-longer-living skull, but here the artist has further complicated the situation by making the lower part of the head a positive presence while the upper part is a negative silhouette—a hollow in the textured background within which the viewer espies, in the distance, the rocky highlands and a starry night sky. Every part is conventionally impossible, yet the eye accepts them all. In a similar conundrum, the powerful-looking figure in the second drawing seems trapped by five walls while the absence of the sixth allows the audience to see him without his being able to escape. His endangerment and safety are one and the same.

Surreal images are not inherently ugly or necessarily unpleasant, but as the title of this show suggests, being unfamiliar does mean they tend toward the uncanny: the strange, unfamiliar, previously unseen, mysterious, and often disturbing. Thus, just as new odors are generally unpleasant until they become familiar, so unfamiliar visual distortions are likely to be unsettling. Zahir’s photograph, “Mind Your Step,” shows this in two ways. First there is his image, in which the model’s legs replace his neck and his shoes become his head. This has an accidental quality that is also a part of the Surrealist canon, but which defies common sense: fold a body in the middle and find its symmetrical quality, but realize that the parts have proper places. Additionally, the setting of the photo appears to be a monument, perhaps a tombstone. Using an instrument of death for a lively purpose is a way of temporarily defeating mortality.

Benjamin Childress, “Hummingbirds”

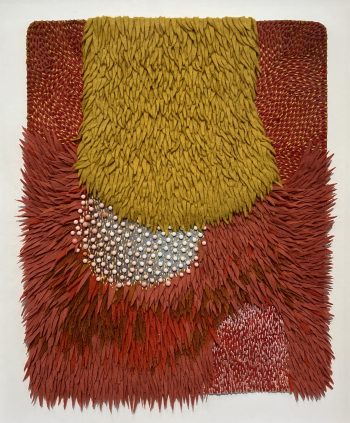

Much of the early Surrealist art defied reason by juxtaposing non-representational images with familiar-sounding titles, thus sending the mind off in a fruitless search for a rational connection. Kathryn Knudsen’s mixed media “Winston” appeals to the tactile senses, which already contradicts the prohibition against touching works of art. Its title, meanwhile, calls to mind an old British name associated with joy, a famous prime minister, a cigarette known for its controversial advertising, and the protagonist of one of the first-ever post-apocalyptic novels, 1984. To add to the mystery, the work feels like it might be alive, or part of a living thing, which lends it an additionally unsettling quality. Meanwhile, Benjamin Childress’s “Hummingbirds” applies a familiar reference to a scene that is anything but familiar: the colorful beings occupying what appears to be an alley in a domestic neighborhood snatch away any reasonable explanation the viewer may naively start to make.

Olivia Dawson’s “Inside outside, outside inside” departs cleverly from convention in its use of a sculpted ceramic setting for a pair of acrylic ink drawings. Her two vignettes depict opposing views of the same domestic bay window, in one of which we are outside looking in, while in the other we are inside looking out. The figure who stands inside covers his or her face, presumably to avert the sight of what is outside—a shirtless man with a bandaged arm, holding a hatchet, sporting antlers and a number of arrows that protrude from his body like a medieval painting of the early Christian martyr Saint Sebastian. The complexity that arises from this seemingly simple opposition of within and without turns a frozen moment into a compound glimpse of a complex, ambiguous myth. Or, it could be a portrait of the viewer choosing not to look through the picture frame at the “surreal” scene it reveals.

Olivia Dawson, “Inside outside, outside inside”

The most refreshing evolution of Surrealism today is surely the departure of women from the limited role of artists’ models in favor of creating their own gender-corrected visions. Alison Stosich’s “That Weight on Your Chest” places a honeycomb and bees on—or in—the fragmented body of an anonymous figure. Neither the honeycomb nor the way the body is broken is all that strange by itself, but together they create a kind of poetry. Sara Luna puts a ship in a woman’s head so that her hair becomes a threatening, stormy sea, thus questioning the title: “It’s Gonna Be Okay.” Cara Jean Hall’s “Overthunk” justifies its title with a curling wisp of smoke that emerges from her subject’s ear. And Erica Houston’s untitled head floats away from its body and passes through a change at least as transformative as emerging from water into air.

- Kathryn Knudsen, “Winston”

- Arash Shoveiri, “Multimedia Desert Painting

Ultimately, writing about Surrealism is a fool’s errand. We know so many more answers to life’s conundrums today than were known in the 1920s, and yet there is still plenty to stagger the mind. All we can do in this space is add a little light and focus to the uncanny moments that are to be had in the gallery. To explain them would be to defeat them. The only thing to be learned is how much the mind wants to explain whatever it encounters. Why else do so many of us follow pseudo-scientific fables and premature fictions that don’t actually explain anything? We may as well join Arash Shoveiri’s figures in the “Multimedia Desert Painting” by plugging into the artificial intelligence that comes down from on high through cables bringing visions that will take the place of the reality that daily puzzles even as it informs us.

There is one alternative to puzzlement that, being joyful, is actually satisfying. The artist who assumes the identity of Elmer Presslee offers his Mystical Forest as an escape from reason. In his forest, he gives us no trees. Rather he uses the Edna Runswick Taylor Foyer’s magically color-shifting glass wall to support the eyes that, in nightmares and horror stories, stare back at us menacingly from within the gloomy forest. There’s nothing to understand here. There are no questions, while the only answers are “Yes” or “No.” To say “yes” in spite of knowing so little is a victory for both the audience and the artist. To borrow one of Cara Jean Hall’s titles from across the hall in The Uncanny Traveler, “She bridled her fear and called it power.” Presslee asks his viewers to do the same. The answer is up to us.

The Uncanny Traveler: Surrealism in the 21st Century and Mystical Forest, SLCC South City Campus, Salt Lake City, through September 26.

Geoff Wichert objects to the term critic. He would rather be thought of as a advocate on behalf of those he writes about.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts

Geoff,

What a beautifully written introduction to Surrealism. And the show looks exciting. I love that surrealism offers a way to explore the many paradoxes we experience daily.

Thanks