Installation view of the Springville Museum of Art’s Spring Salon, with a variety of works including, far left, Margaret Abrahmshe’ s”The Reader.”

There are any number of categories into which the variety of fine and visual artists, and their works, can be divided. There are characteristics of the artists themselves: are they men or women? Are they young and newly fledged (like those in Artists of Utah’s 35×35 exhibit) or old, accomplished, and even celebrated? Curiously, while the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints actively discourages labeling its members “Mormon,” that is the more common term when it comes to artists. More recent categories include association with particular groups, like faculty of a specific school, or broader categories like the American Association of University Women, which biannually exhibits works by its members.

Then there are the media employed. Watercolor and oils are often mentioned, while the Face of Utah Sculpture focuses on three dimensions. And then there are the so-called crafts, which until some time in the last century were regarded as “decorative” and not “meaningful,” that is, concerned with appearance and not beholding of content. Clues that these were being elevated included their names: clay became Ceramics, a number of glass techniques were united as Studio Glass, and fabrics were anointed as Textiles. Even within these categories, there were hits and misses. Weaving, in no small part due to its interaction with mechanical processes, rose to the top, while basketmaking, a chaotic category associated with indigenous variation and little else, was among the last to become respectable.

Installation view of Sara Luna’s “Chat GPT, Tell me what to do with this pain.”

At the Springville Museum of Art, the thinking goes that art is art and it’s all valid, which among other things makes a visit incomplete unless it includes a tour of the upstairs, where their marvelous, omnivorous permanent collection is shown in rotation. In the meantime, downstairs, the Spring Salon is in full flower. Maybe it’s because last month’s NCECA extravaganza sensitized us to the possibility of foregrounding a medium we don’t normally get to indulge in, but 15 Bytes is suddenly seeing a lot of textiles wherever we look. Here are some I noticed at the Salon.

Pride of place goes to Sara Luna, and not just because her astonishing self-portrait, “ChatGPT, Tell me what to do with this pain,” hangs in the first spot of the first gallery of the Salon. In fact, her large, monochromatic, startlingly illusionistic weavings have been hanging very much like paintings, among paintings, since they first began appearing at least three years ago. Her work has been discussed in these columns a number of times, and it’s fair to say she’s made the transition from art that recalls its origins in craft to art that stands on its own.

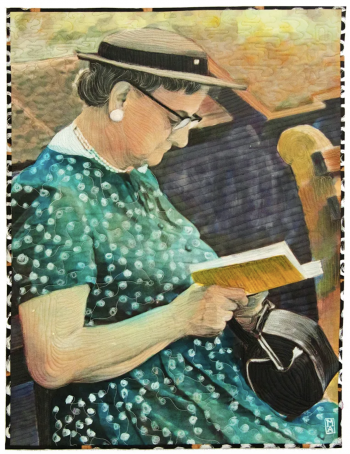

A very different technique is used for similarly intended, yet visually contrasting results by Margaret Abramshe. In “The Reader,” a painting on fabric that uses a technique she appears to have invented, she engages in what she calls “a conversation with history” on the topic of issues faced by women, as revealed in photographs she found in the collection of the Library of Congress. The Library is one of the irreplaceable resources currently endangered by the new administration in Washington, D.C. Specifically, Abramshe is using photos of American city life taken in the middle of the 20th century by Angelo Rizzuto, who in 1967 bequeathed 60,000 images to the Library he called his “Anthony Angel Collection.” Abramshe turns a chosen image into a painting on linen cotton canvas, then drafts contours and patterns over it with multicolored stitching. The color-matched thread as much as disappears into the painting, leaving behind a surface reminiscent of impasto paint application or bas relief. As is often the case with exploratory techniques, the result should be seen in person. Across a gallery or from a moderate distance, the subtle-but-elaborately three-dimensional surface seems animated in a way that draws the viewer in for a closer look.

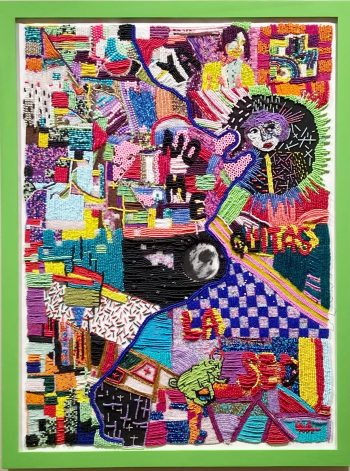

Of course there are other things besides visages and expressions of emotion that art can represent. In “Ya No Me Quitas La Sed,” Bianca Velasquez employs one of the oldest textile media still in use, beadwork on canvas, to make visible feelings elicited by a Spanish-language song, the lyrics of which describe “a thirst that just won’t quit me.” Here we witness the ability of art to take something literal, like a need resulting from an addiction to alcohol, and expand it into a universal experience. You don’t have to be an alcoholic to appreciate an unquenchable, metaphorical thirst: just being human will do. At the same time, once again here photography diminishes art, turning 200 hours of hand-beading, done over a year on a canvas almost as tall as the artist, into a thumbnail so crowded the details may get lost. Popular music is one way of achieving relevance, but there are others, as when Velazquez painted an image from her favorite David Lynch film, “What did Jack do?” Just as she did in “Ya No Me Quitas La Sed,” where the beaded words of her title are threaded into the final work, the painting of the late film director makes use of the hand-painted phrase, “It’s all like a crazy nightmare to me now,” laid out so the setting emphasizes the last three letters of “nightmare.”

- Margaret Abramshe, “The Reader”

- Bianca Velasquez, “Ya No Me Quitas La Sed”

Following an artist from her textile work to her painting is nowhere near as backwards as it may sound. One thing scholars are beginning to recognize is how great was the impact of craft ideas and techniques on mainstream art. Enthusiasts for Southwestern American art may appreciate, or at least have puzzled over, the paintings of Agnes Martin, but in truth paintings that can be confused with designer carpets are only a part of the story. No artist did more to liberate color in painting than Paul Gauguin, and it’s now known that before he gave up monetary future’s trading, he hung the walls of his home with carpets, which almost certainly influenced his future art-making.

And finally, it’s worth remembering that material is different from medium. Julie Berry’s “Temptation” is a collage made of paper, a medium and material that were adapted from crafts as part of Picasso and Braque’s early 20th-century invention of Cubism. But the way Berry uses collage is further influenced by the materials of quilting, using patterned papers the way a quilter exploits the patterns manufactured into the fabrics that comprise her raw material. It’s how she suggests the existence of a boundary in time as well as space that her subject visibly contemplates crossing as she ponders the thing that tempts her. It’s another example of the importance of seeing the influence of textiles regardless of the materials actually in use.

Julie Berry, “Temptation”

101st Annual Spring Salon, Springville Museum of Art, Springville, through July 5.

Geoff Wichert objects to the term critic. He would rather be thought of as a advocate on behalf of those he writes about.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts