Detail from “Sitatapatra,” Tibet, dated 1864, pigments on cloth

The visual cultures of the Himalayas are the rock-and-roll of Buddhist art. Wrathful deities wear flaming hair and skull garlands. Tantric divinities intertwine their limbs in sexual embrace. The searing mineral brilliance of cinnabar and azurite compete for the viewer’s attention. And ritual cups made of human craniums compel us to think about the impermanence of life. It is all meant to hasten the practitioner to enlightenment, or the true perception of reality. If Zen rock gardens hum our way to awakening, Himalayan art propels us with the pulse of heavy metal.

The fantastic exhibition Gateway to Himalayan Art, at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, introduces us to the cacophonous visuality of this region, which includes Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan and Mongolia, through a stunning selection of objects from one of the finest repositories of Himalayan art in the United States, the Rubin Museum in New York City. What makes this exhibition even more special is that the Rubin permanently closed its physical doors in October of 2024, becoming a museum without walls. Traveling exhibitions such as this one are now the only opportunity for viewers to engage with their artworks. The UMFA show is on view until July 27, 2025.

Installation view of the “Symbols and Meanings” section of Gateway to Himalayan Art at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts. The section introduces viewers to Himalayan divinities through thangkas and sculptures, including gilded figures and richly detailed narrative scenes. Image courtesy of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts.

The exhibit is divided into three broad themes: Symbols and Meanings introduce us to the rich pantheon of divinities in Himalayan art. Materials and Technologies explore how metal, clay, stone, wood, cloth and paper are manipulated to create images. And Living Practices connect the historic and current functions of Himalayan art. Let’s begin with Symbols and Meanings, which cover the subthemes of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Tantric Deities, among others. The exhibit has examples that illustrate each divinity type, with occasional didactics and QR codes that link to an extensive digital platform developed by the Rubin Museum: Project Himalayan Art.

Buddha Shakyamuni, Gilt copper alloy, Tibet, 15th century, 7 ¾ x 5 7/8 x 4 7/8 in. Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Gift of Shelley and Donald Rubin.

The standout object in this section, for its beauty and historical significance, is a Buddha Shakyamuni from the 15th century. It is the first image you see as you enter the exhibit. Made of gilt copper and standing seven and three-quarters inches high, it was most likely intended for personal worship. Echoing its prominent position in the gallery, the Buddha Shakyamuni is also preeminent in Buddhism as the historical figure who achieved enlightenment in the 5th century BCE. His teachings on the nature of suffering and the ways in which to escape it would become the foundations of Buddhism. As an artwork, it also provides a blueprint to read Buddhist art through symbols, or iconographies. Several of these symbols identify this as a Buddha, or an enlightened being, rather than a Bodhisattva, or a nearly enlightened being that remains in this world to help others. First of all, the head is not crowned as with Bodhisattvas. Rather, there is a cranial protuberance, or ushnisha—a symbol of wisdom. The head is also covered with snail-like curls, a reference to Shakyamuni cutting off his princely locks when he left his palace to seek the nature of truth. Yet another sign of his renunciation are his elongated earlobes, indicating the weight of his former jewels. He holds a begging bowl in one hand, an object of humility, and his other hand touches the earth.

This hand gesture, or mudra, is at the center of the image’s iconography. It is a direct reference to a specific moment in the Buddha’s biography, when at the age of 35 he sat down under a bodhi tree and vowed to find insight into the true nature of reality. When distracted from maintaining his concentration by Mara and the forces of evil, Shakyamuni pointed his hand to the earth and called it to witness all his previous good actions. The earth responded that he was indeed ready to achieve enlightenment and washed away Mara. From this point onward, Shakyamuni could be properly called the Buddha, or the awakened one. It is important to remember the correct meanings of this iconography in the face of pop cultural readings of Buddhist images as symbols of peace, tranquility and even bliss. A Buddhist viewer would read this image as reflecting a path to enlightenment that they too could achieve. This path was summed up by the Buddha following his awakening: existence is suffering; there is a cause to this suffering; there is a way to cease this cause; and the path to this cessation is through the Eightfold Path.

The next section of the exhibit, Materials and Technologies, contains compelling step-by-step displays that take us through the exacting processes of making thangkas, or paintings on cloth, and metal sculptures through the lost wax casting technique. These are excellent presentations that take us behind the scenes and put us into the shoes of frequently unnamed artists. Traditionally, Himalayan painters were spiritually advanced people who were vehicles that transmitted the rules of proportion, or iconometry. Himalayan art rarely expressed the unique style of an artist or workshop. Having said that, regional styles did develop given that the Himalayan region bordered on the influential cultural spheres of China to the East and India to the West and South.

The “Materials and Technologies” section includes a step-by-step display of the lost-wax casting process, offering insight into how Himalayan bronze sculptures are created—from wax model to finished form. Image courtesy of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts.

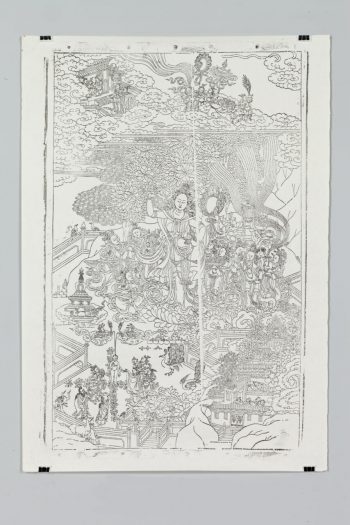

- Buddha’s Birth, from a set of the Twelve Deeds of the Buddha, Print from a woodblock, ink on paper, Derge Printing House, Kham region, eastern Tibet, after 1960. Rubin Museum of Art, Gift of William Hinman.

- Birth of the Buddha, from a set of the Twelve Deeds of the Buddha, after a carved woodblock composition attributed to Purbu Tsering of Chamdo (active ca. late 19th century, pigments on cloth, Tibet, 20th century, 29 ¾ x 19 ½ in. Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, gift of the Shelley and Donald Rubin Foundation.

You can see an example of regional style in a side-by-side comparison of “The Birth of the Buddha” along the back wall of this gallery. On the right, there is an ink on paper print from a woodblock from the Derge Printing House. On the left is a version painted on cloth that is clearly modeled on the print on the right. While the print placed under the thin cloth would have guided the composition and outlines of the painting, the use of colors would have been left to the artist. It is in the use of these colors that we get the sense of this painting as coming from Kham or the Eastern Region of Tibet. Note, for instance, how the green mountains and blue-white clouds are all contoured with back shading, as if these forms are floating on the surface of the painting. This, along with the use of Chinese balustrades and architecture, mark this as a Kham work.

The final section, Living Practices, is arguably the most fascinating part of the exhibit. You see powerful ritual implements meant to support the practitioner in their quest for wisdom and compassion, the union of which leads to enlightenment in Himalayan Buddhism. But you also see secular objects from the 19th century, such as medical instruments and illustrations, which challenge the stereotype that Himalayan art is strictly religious. Indeed, this negotiation between the secular and the sacred is best exemplified by the last object in the exhibit, a shrine cabinet, or chosham, that occupies its own space and soundscape at the end of the exhibit. This is an intricately carved and elaborately painted work covered with decorative floral motifs and fierce protective deities. The installation at the UMFA includes sacred books, or pecha, in the top niches, but lacks the sculptures of divinities that would have occupied the lower niches. Chosham were how the sculptural Buddhas and Bodhisattvas found throughout the exhibit would have traditionally been displayed in Himalayan monasteries and homes. Nevertheless, and whether it is intentional or not, the absence of icons in a shrine meant to house them asks us to consider a fundamental philosophy in Buddhism, that of sunyata, or the emptiness underlying the existence of all things. What better way to sum up an exhibit of sacred art in a secular space?

Shrine Cabinet (Chosham), wood and mineral pigments, Tibet, second half of 20th century, 87 x 69 x 27 in. Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Gift of Kingdoms Unlimited.

Gateway to Himalayan Art, Utah Museum of Fine Arts, Salt Lake City, through July 27.

Winston Kyan holds a PhD in Art History from the University of Chicago. He is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Utah, where he offers courses on the arts of Asia and the Asian Diaspora.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts