Brian Kershisnik, “Sens de l’Orientation” (sense of direction), 40×30 in.

Brian Kershisnik is among the more generously talented artists presently on the Utah scene. Not only does he paint and make prints, but he writes songs that he then performs and records with a group of musicians. From there, he made the natural leap to poetry, which he has published. Several times a year, Kershisnik addresses his admirers, either in a museum setting or at a venue such as his studio, and there is always an eager audience for these performances. Although he has not been observed to perform stand-up, his witticisms are repeated widely and written down for safe keeping. Asked how he can stand to sell his works of art, which are likened to his children, he replied, “Yes, but they are his adult children.”

It’s ironic that when Kershisnik started out in art, he initially failed. While there is some disagreement about the details, after training as a printmaker, his first foray into the commerce of art was in ceramics, and it was apparently, generally agreed that he was not a potter. What makes this truly ironic is that years later, when he began sculpting portraits and figures to be cast in bronze, his expressive approach to the clay made the result much more than just another version of the painted works that he sometimes invokes in three dimensions.

Brian Kershisnik’s “The Difficult Part” on the lawn of David Ericson Fine Art in Salt Lake City. Image courtesy of David Ericson Fine Art.

While many Kershisnik sculptures have been small enough to sit comfortably on a desk or mantle, others have included life-size busts or tabletop ensembles of full-length figures engaged in, to take one example, planting a garden. But those arriving to hear him speak and to see his latest paintings at David Ericson Fine Art in late September may have been struck by the sight of two life-sized figures on the lawn in front of the building, engaged in what has become a familiar activity—dancing as if they were, in fact, weightless.

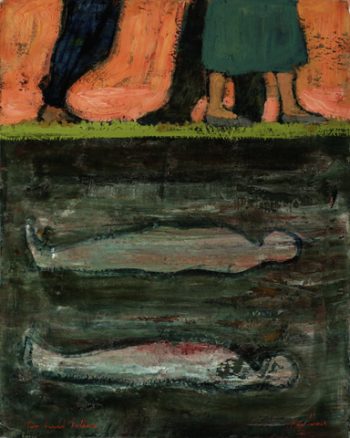

There are almost always Kershisnik sculptures included in any exhibit of new paintings, and while viewers probably come for either their favorite painted subjects, the artist’s evolving treatment of these, or his ceaseless painted exploration of human life and its truths, reflected in wholly new visions, these bronze pieces have become an ever-more important part of his body of work. Like it did to most of us, the pandemic forced Kershisnik to reconsider his past choices and future options, and while his lust for life remains undiminished, it’s clear that he has given much thought to the fragility and even the fatality of life. A good place to see the change is “Two Buried Fathers,” in which the feet of three living persons are seen to walk over a cross-section of the ground beneath them, through which are seen to be buried what might be members of two generations of ancestors, one of whom may have died in a war. One possible reading, which is by no means mandatory, is that the arrangement of figures from bottom to top may signal the passage of time as a matter of successive generations.

Another painting that seriously considers life’s less salutary side is “Various Injuries,” in which a woman, herself injured, tends to the wounds of two men, one of whom attempts to comfort her simultaneously. Then there is “Complicated Gathering,” in which three persons, possibly the owners of the three sets of feet seen in “Two Buried Fathers,” engage in some serious negotiations while four dogs frolic behind them. Things were never all that simple in Kershisnik’s world, but what was often play in the early years is now more likely to involve what he calls “the difficult part.”

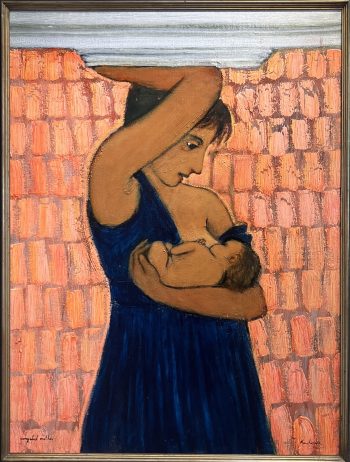

- Brian Kershisnik, “Caryatid Mother,” 30×40 in.

- Brian Kershisnik, ““Two Buried Fathers,” 30×24 in.

Perhaps the most revealing expression of this emblematic view of life is the one that not only appears three times among the works in this show, but which gave the entire exhibition its title: “Holding Things Up.” In this composition, which the artist has been exploring for awhile now, a living woman acts as a caryatid, a term which refers to the architectural use of a human body as a column in support of a roof member. In these versions, she may be holding, or nursing—and either way surely “holding up”—a child, but at the same time, symbolically supporting the sky, as has often been said of women in modern times (most famously perhaps by Mao Zedong, who originally credited women with holding up more than half the sky). It’s not that easy for a man to give credit to a woman without seeming to condescend to her, but simply placing her in a position of such responsibility, whether sharing the injuries or getting along with the tasks at hand, without fuss or expectation, seems like a possible approach.

Another element that has assumed greater importance is the narrative that propels a painting. In the past, the audience was invited to contemplate a relatively static scene: an individual or group caught in what was often a mysterious, even baffling scene. Compare that to “Of Course I Would Do It Differently Today.” Here a woman stands, with her back to a table, yet turns her head to peer back at what appears to be a letter on the table. She refers to an earlier event, finds herself at fault, and says that were it possible, she would attempt a different outcome. Time, it seems, has taken on a role in this more recent version.

Similarly, something revolutionary—though perhaps not so new to this artist—takes place in “Sens de l’Orientation (Sense of Direction).” Here the subject invokes a fact not many works of art refer to: the world outside the painting’s frame. In fact, it really wasn’t until the introduction of photography, in the era of the Impressionists, that the visual world took note of what happens when something is caught on the edge of the photo, and it became a subject for the artist. While in this work the artist lays claim to a sense of direction for the subject, so far as we’re concerned he may be adding to our feeling that we have inadequate information.

Every work of art by Brian Kershisnik is the product of his inquiry into the visual world and its capacity to possess and convey knowledge. It sometimes feels as though a catalog of all of the implications of even one of these essays would rival the Encyclopedia in scope. Most of what happens to those who people his world has happened to his audience: forgetting the question, changing ones mind, having to relearn what has been forgotten, straying off course, having a gift spurned (by a cat, no less). But in these colorful and focused images, they take on virtues and a dimension of importance we may struggle to experience in our lives. Yet in the art of Brian Kershisnik, a lost sense of perspective may be regained.

Gallerist David Ericson speaks with two patrons in front of Brian Kershisnik’s “The Whole Thing,” 74×84 in.

Geoff Wichert objects to the term critic. He would rather be thought of as a advocate on behalf of those he writes about.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts