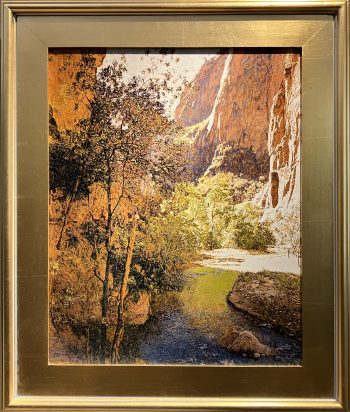

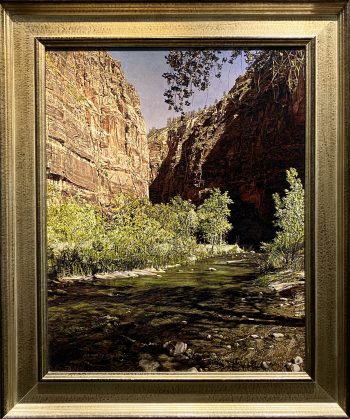

Many who are susceptible to its charms consider Zion to be possibly the most beautiful of our national parks. While the nearby Grand Canyon is better known, Zion inverts its effect, becoming much more intimate. We approach Grand Canyon from the top and gaze down in wonder. Zion is entered at the bottom, in a space enclosed by fierce stone cliffs, but which is less like a desert and more like a walled garden. The difference is clearly visible in “In the Shade/Zion,” an oil painting that is one of nearly a dozen currently being exhibited by artist Michael Aitken in the gallery at the Anderson-Foothill Branch Library. While another image, simply titled “Zion,” essentially stands us outside, by the river, as we look into the rugged spires central to the park, “In the Shade” contrasts nearby trees that sparkle in indirect sunlight with a grove on the other side of the creek and further away, in full sun that makes the grove seem to burst into flame. Like most of Aitken’s splendid effects, his handling of the light must be seen in person; it does not show to full effect in mere photographs.

While the light is compelling, the most striking effect of this artist’s brush is surely the textures he imports into the rocks, foliage, and even the water. That he does this, with inevitable if slight variations, in both his oils and his watercolors, speaks to his having achieved control over the techniques that achieve it. Having both a BFA and an MFA from BYU doesn’t explain this, though it testifies to his disciplined approach. But there are many painters that studied in the same school and none has anything like the same palpable feel in the brushwork, which recalls Baroque masters like Rubens in its implausible-but-undeniable realism.

Aitken agrees with the suggestion that, given Utah’s preference for the landscape in art, the artists should try to find something original to say about it. For him, it’s how the location made him feel when he encountered it. The light doesn’t just illuminate the scene, but warms or gives away the lack of warmth. Comparing the snow-capped spires of “Bryce” to any of the other scenes reveals how, in the midst of a heated gallery, an attentive viewer may yet feel a chill.

- Michael Aitken, “In the Shade / Zion”

- Michael Aitken, “Into Shadow / Zion”

Here a word about Aitken’s choice of the Anderson-Foothill Branch is appropriate. Only a few blocks away, at “A” Gallery, the audience is treated to works by as many as two dozen artists, which are routinely moved about the rooms in order to give a more complete sense of how they look in context. Not so at the Library, where bare concrete walls isolate the work of a single artist for absolute clarity of vision. You may have to take one home to find out whether it works when surrounded by your lifestyle, but you will have witnessed its pure form at the start. When I first saw this room, I was unsure about it. But with repeated exposure, I remembered there is a reason why, as the influence of royalty and the church gave way to individual taste, fine museums increasingly went with fewer works on neutral-colored walls. Even New York’s Frick, in its recent expansion and remodeling, relies less on its wealthy founder’s original hangings of his invaluable masterpieces, and instead shows them as the unique and unimpeachable objects they are.

One of the thrills to be had with work that takes itself so literally is the opportunity to see something in a painting previously seen in life: not so much an interpretation, but what amounts to a portrait of a place. At the opening, a woman was enthusiastically pointing out “Orchard, Capitol Reef” to complete strangers and indicating just where she had stood when she was there in person. Clearly, painting and the landscape still has the magic for her that it has for so many, beginning in childhood. My parents had a painting of a tree gone red in autumn, standing by a pond. Though it meant nothing to me at the time, I know now that it was a watercolor, because whenever I see that transparency in a painting today I am transported back to those years of rapture.

And rapture is what I expect most viewers will experience with Michael Aitken’s Utah scenery. The specificity and attention to the range of appearances, along with the many different ways natural light will affect different parts of the same scene, will all but guarantee that these views will never lose their freshness, never cease to please the eye.

Viewers at the Anderson-Foothill Branch Library gallery take in Michael Aitken’s landscape exhibition, surrounded by Utah scenes rendered in oil and watercolor.

Michael Aitken: Landscapes, Anderson-Foothill Branch Library, Salt Lake City, through November 28.

Geoff Wichert objects to the term critic. He would rather be thought of as a advocate on behalf of those he writes about.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts