Stacy Phillips, “Still We Rise, Maya Angelou”

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Maya Angelou’s flawless quatrain receives a response in Stacy Phillips’ Let’s Get Personal: Faces of Humanity, currently on view at Finch Lane. In “Still We Rise, Maya Angelou,” nearly 16 square feet of work surface has been assembled from numerous odd blocks which, once heavily handwritten upon, accept the addition of 36 vivid and unnaturally colored heads of anonymous men (and a few women?), then another layer of scribbling added over that. A viewer who saw this work before any of Phillips’ others might reasonably question their being called “portraits.” But seen in the context of the rest of Let’s Get Personal, the whole work may rightly be seen as an attempt to push the portrait as far as possible away from its finite, limited role in identification and into the artistic territory Phillips refers to as “the common ground we share as humans.”

There are, in fact, 32 distinct works here, half of which are collected together as the “Raw Surface Series #1-16,” each 11×14 inches. The rest, with the exception of “Still We Rise,” initially resemble conventional portraits, though in fact they would seem to depict subjects who never have existed. What they all have in common is less concern with identity and a far greater interest on the artist’s part in the elaboration of their materials. That, along with her intuitive relation to those media. What can she use and how can she use it? While her experience is a part of the process, she equates it to curiosity. What she can make of it.

Stacy Phillips, “Raw Surface Series #1-16”

Where the envelope, so to speak, gets pushed the furthest is in the Raw Surface Series. Here she glues oddly shaped pieces of various materials in seemingly random places on her panels. Some of these she then paints on, while to others she adds printed papers of various sorts. The paints, when they happen, follow an entire range of mark-making practices. Some of the faces are almost conventional, while others recall the legendary critical dismissal of Marcel Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase”—that it resembles an explosion in a shingle factory.

In the rest of the gallery, the titles are as clever and challenging as the images. A palimpsest comes about when an image is scraped off a parchment page so it can be reused for a new picture, and in this way “Palimpsest of Kin” suggests that the family resemblance between the two women—sisters, one wonders, or mother and daughter?—could have been generated by replacing one face with another that shared the same influences.

In an unacknowledged pair, meanwhile, a woman is said to be “For Those Who Weigh Without a Crown,” while a man bears up under “The Weight of the Invisible Crown.” Picasso’s famous 1905 portrait of Gertrude Stein might come to mind here, more or less in the way that friends of Stein said no one would see her likeness in the finished work. Picasso’s response that “SHE would” proved correct, while Stein understood from the first of 80 posing sessions that in the beginning it would’t look much like her—but would in time, as portraits inevitably must once they replace access to the original. Set aside the issues raised by the verisimilitude of painted portraits and it becomes apparent these portraits have so many charming details it could only seem stingy to dwell on matters of mere resemblance.

- For Those Who Weigh Without a Crown

- The Weight of the Invisible Crown

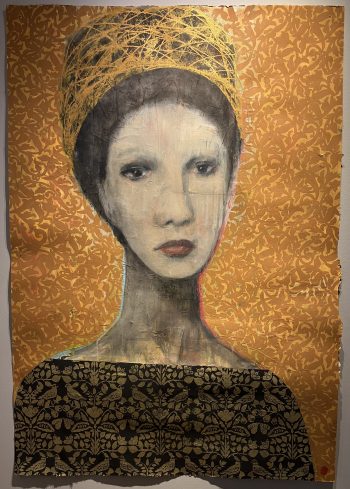

Another pair, though maybe not planned, includes “Can You Hear Me Now?” and “Silence.” In the former, the bold, even explosive style of drawing, with dramatic streaks and lots of visual noise, seems to fill the space with sound. In the second, the emotion being delivered seems more to do with an intense, but interior voice. Finally, in “Pieces of Me,” decorative bits and pieces and whole facial features seem to have been transposed and visibly attached to another seeming picture of royalty. Just which way these pieces “of me” are going isn’t clear, and may just be up to the viewer to decide.

Stacy Phillips, “Pieces of Me”

There’s really no mystery here. Portraits and figures offer the artist the maximum freedom to create images that remain both relevant and engaging. Among realists, portraits of themselves and others are surely among their most popular images. But these faces are not only extraordinary, but at the same time fictional characters free from narrative. All Stacy Phillips need do is make sure her imaginary subjects come off as so interesting, seductive even, that their lack of correspondents in the real world simply doesn’t matter.

Let’s Get Personal: Faces of Humanity, Finch Lane Gallery, Salt Lake City, through October 31.

Geoff Wichert objects to the term critic. He would rather be thought of as a advocate on behalf of those he writes about.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts