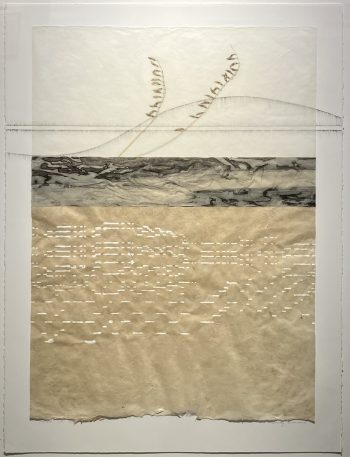

A selection from Sandy Brunvand’s “Songscapes” series, where the rhythmic voids of piano rolls form a visual counterpart to desert topographies and cloud formations.

If there is an artistic form that the Utah audience might survive seeing less of, surely it’s the landscape: a medium that is tolerant of exploitation almost to a fault, and which has seemingly been shown in every way imaginable. Of course, discerning individuals might argue that what’s needed isn’t fewer images of this planet on which we dwell, but more original—more genuinely ground-breaking, so to speak—ways of depicting it might be welcome. Enter Sandy Brunvand’s Ecotone, 35 landscapes that variously depart from pretty much all that has preceded them, currently showing at Finch Lane. Despite what some viewers may be thinking, Brunvand has waited at least a quarter century to offer her take on the larger vista, and the story of her progress to this point is worth recalling.

Brunvand has always taken the Earth—or as she has it, “this place in which I dwell”—as her subject. But it’s not been as a landscape. As she explains in her artist’s statement, in several previous appearances in 15 Bytes, and in Utah’s 15, for which she was selected by the popular vote by our readers, her process commences almost every morning with a hike along the Bonneville Shoreline Trail, which runs horizontally, in consequence of its formation around a giant lake, nearby her home in Salt Lake City’s Avenues. Always accompanied by one of her dogs, she closely observes the surrounding flora and fauna. This exercise brings her close to the ground, where she and her companion discover plant and animal inhabitants that share an ecological niche, which she characterizes as part of an extensive “ecotone”—the late Florence Krall’s term for the boundary between two or more environmental niches: in other words, a zone where the lives of the denizens are likely to be in a state of flux.

Her current work naturally comes out of the years of drawing, printmaking and unceasing exploration of her media that preceded it, but it also sums all that up even as it carries it forward. Take, for example, the Ecotone subtitled “Desert Songs #3,” which, like so many of the works here, is done in a mixture of media on a salvaged player piano roll. Moving from near to far in the represented vista—in other words, from the bottom to the top of the panel—the viewer first encounters the desert floor. It’s unlikely that anyone but a scientist has spent more time examining what goes on in those first few inches above this ground. Her drawings of the elaborate life dwelling there are full of charm and experience, but here she’s chosen to saturate antique paper with ink that, as it soaks into the wood fibers and then dries, brings out how some very different materials can nevertheless appear alike.

- “Ecotone Trail Song”

- “Desert Song #3”

Here we encounter one of the paradoxes of the Southwest which, having been carved down into an ancient sea floor upthrust by continental transformation, is more flat than we, with our two meter height, realize. With the exception of occasional towers and spires, this land is horizontal, and the ridge appearing near this trail, which lies to the north of Salt Lake City, is a typically low feature. But above this horizon, the sky assembles and holds layers of clouds that pile up like great mountains and are recollected here in various colors of torn paper. By this point, the viewer may have noticed, but will surely be responding to regardless, the way the artist has matched her growing perspective to the pre-existing pattern of keys cut in the paper, thereby uniting the image with exceptional power.

As a musician, specifically a blues and bluegrass performer who specializes in the mandolin, Brunvand’s feeling for the music of the desert begins with the pace and rhythm of her steps as she hikes through it, but extends in some fourth-dimensional sense to the pattern on the piano roll, which, while only decipherable by the mechanical player, must be visibly related to the music as well, even if not in a way viewers can directly comprehend. The resolution of this conundrum is visible in the way she has painted it.

Sandy Brunvand, “Dog, Ink Trails, and Wash”

Anyone who remembers the early, delicate drawings of tiny plants, sometimes alive and at other times only their dried skeletons, will probably recognize their occasional appearance here, like the meticulously cut out and appliquéd stem that runs through the lower portion of “Desert Trail Song.” Other past inventions appear in “Dog, Ink Trails, and Wash,” one of the most physically complex pieces here. The graphic character of collected dog hair was one of the artist’s personal and somewhat confrontational choices, and “Dog” refers to the evidence of the one who is missing—hair from her companion that is laminated into the upper portion. Connecting the upper part to the main image are some of the more subtle line patterns she created. They say less about the muscles of her arm and the behavior of liquid ink on paper and more about mathematics and ideal form. Yet these drawings, too, call attention to their human source. She showed them alongside those of her colleague, Al Denyer, whose elaborate drawings, some of which take more than a year to complete, share this inordinate power of suggestion—existing in the eye and the mind at the same time. They might be an early appearance of this concept of the “ecotone,” in that they exist in two dimensions—thought and action—simultaneously.

When Brunvand began this practice of drawing from nature, she’d chosen to make the drawings life-sized, and so, small, and played with various forms of presentation in an ever-increasing repertoire of media and contexts. She might have mounted these just as they were in small frames, or used techniques like chine collé, drawn from her active involvement in printmaking, to insert them into other works. Another example occurs in “Above and Below,” where dramatic-yet-generic roots appear like an inset or a transparency laid over a range of near and far effects. Construction-based, possibly from her days as a ceramic sculptor, she assembles her images from independently created parts. Here the best characterization might be “one thing leads to another.” For instance, she’s always employed one of the 20th century’s primary “upscaled” craft media, collage, but often substituting alternatives to glue. One of these is staples, and it’s not clear whether having boldly stapled some small parts together, she started making designs out of the joints, or if she had already discovered the decorative possibilities of staples on their own. There’s an analogy here to the technique of machine sewing on paper, which became another popular innovation around the turn of the millennium.

Another example of how one thing can lead to another came about during her Divisive Landscapes project, which saw her collaging newspaper headlines onto other media, such as prints. Eventually, she decided to use a typewriter to copy the words directly onto what had previously been the support, which created more of a sense of immediacy. While there are no typed headlines among the Ecotones, the principle is everywhere. Instead of seeming to join two things, an act that joins them physically but often more clearly separates them in the mind, the typewriter created impressions directly into the work, along with mistakes and other artifacts that underscore how these have now become a single original.

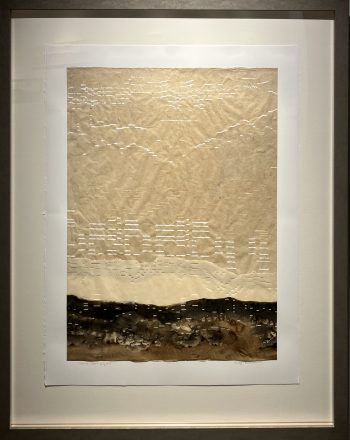

Selections from the Songscapes series.

Among the strongest works here, the eight paintings called “Songscapes” share a reference to the music one might imagine while gazing on stone and sky, implied by that patterning of slots in the paper on which they are painted. Throughout the Ecotones, their presence may play more than one role in the overall effect. It’s possible Brunvand is working, consciously or not, towards the shared goal of breaking down the distinction between realism and abstraction that can be seen so often in today’s art. If so, she is taking a very different tack than are those painters who use, for examples, a loose or spiky brush to effectively loosen up a realistic image, or to make it more emotionally expressive, or else to lend some real world reference to the experience of entirely invented abstraction, which has proven less universally satisfactory than its early exponents expected. Instead of merging the two formerly irreconcilable ways of conceiving and executing an image, she seems to employ both in the same space on the canvas while keeping them apart, like parallel lines that go the same place without ever meeting. The presence and focus on a geometric structure is fully present in the same space as the convincing illusion of land and sky.

A trio of Ecotones that are not complicated by uncertainty about how to read the slots includes three images of trees that seems rooted in the elementary printer’s technique of running a leaf through the press to produce a copy with an uncanny presence. “Ecotone-Leaf and River,” “Ecotone-Family,” and “Ecotone” are full of aqueous textures, luminosity, and shadow, all things that Brunvand mastered long ago, but only now brings to bear on the landscape as part of her exploration of boundaries between environmental niches.

- “Ecotone-Leaf & River”

- “Ecotone-Family”

- “Ecotone”

In literature, we speak of a bildungsroman—a novel that tells the coming-of-age story of the protagonist. There’s a parallel in that to the way Sandy Brunvand has retold the story of her education in, and reinvention of, her art through these explorations in print, paint, and drawing of the history of the land. And it is its history, almost its biography, that we see when we look at it in its naked form—a skeleton of rock undressed of forests and fields. It’s worth observing that of all the techniques she’s bent to her purpose or outright invented, the one that contributes the most is the one that most closely approaches the way our senses and especially our brains work: collage. One practical limit to how artists mix their technical means together is that they don’t always work well together on a single canvas or sheet of paper. One work among the 35 makes the point in a way that draws attention and professional appreciation to it. The aptly titled “Song Train Residue” consists of a single piece of Mylar parchment—a plastic sheet laid down to protect the work surface in the studio. This one has gone a long way with the artist who employs it, who admits to having long wanted to include it as an essential part of the work on display.

And so, in the end we return to the connection, so strongly made here, between the subject and the art it occasions. And the thousands of hours spent in praise of the product of millions of years of natural history leads us back to the source … to the land and its eternal, restless self-creation. It’s a song in praise of the fecundity not just of life on Earth, but of the Earth itself. The way Nature lays down layers of rock over millennia is acknowledged in the way Brunvand lays down layers of painted paper on which she has recollected a day of work here, and then another there that contrasts and complements it. The landscape that results is collaged together just as the sandstone and limestone of the desert Southwest has been built up and cut through by small amounts of water flowing over elaborate centuries. Sandy Brunvand has not just refreshed the landscape; she’s reinvented it, and like a novel among short stories, it’s worth taking more time to both see and comprehend what she has made.

Sandy Brunvand: Ecotone, Finch Lane Gallery, Salt Lake City, through July 25.

All images courtesy of the author.

Geoff Wichert objects to the term critic. He would rather be thought of as a advocate on behalf of those he writes about.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts