Clint Call’s “Reassembled Dog” points towards J. Amber Egbert’s sculptural rendering of a Giorgio Morandi painting at the latest iteration of The Face of Utah Sculpture.

“What is the answer?” And after a pause, “What is the question?” These famous last words of Gertrude Stein, spoken from a hospital bed to her lifetime partner, Alice B. Toklas, in 1946, seem to echo the question asked every year for the latest quarter century by The Face of Utah Sculpture. This open-ended, non-juried exhibition, founded by Dan Cummings and held for the last 21 iterations at the Utah Cultural Celebration Center, never fails to ask “What is sculpture?” And the responses it provokes from the Utah artist community never fail to provide new answers.

For instance, in “Canvas to Clay,” the always-reliable J. Amber Egbert, possibly provoked by the limited information provided by Giorgio Morandi’s 1953 still-life painting of nine clay vessels, first painted her own exploratory version of Morandi’s “master copy” and then reproduced his nine clay vessels, thereby demonstrating the greater fidelity of sculpture to what the artist saw. Might she be saying a painter can force a viewer to see the world in one way—his way—while a sculptor can reveal it in all its dimensions? That she can bring the subjects into the room in a way the painter cannot?

Randy Kimball’s “If I Had A”

Whatever the artist has in mind, art lies in giving it a material expression. While essential, those materials can be subtle, background information, or they can come right up front, as happens in Randy Kimball’s meticulously laminated and shaped “If I Had A,” in which the layers transcend decoration to deliver a subject: the flag as hammer. While it could well be a patriotic call for order in the land as well as in the court, there is the inescapable potential for national feelings to become a cudgel, for the would-be patriot to bludgeon others into agreement. The choice is implicit in the art.

Other major social comments include Frank McEntire’s “At Our Common Doorstep,” in which a pendulum invokes the question of balance between the manufactured environment and the natural world. Other members of the Wasatch Assemblage Ensemble (as I like to call them) ask related questions. Perching a globe uncomfortably on a chair in “A Seat at the Table,” Abe Kimball suggests that vital decisions about our fate are made by those who sit around and take meetings most of humanity is not invited to attend. Vincent Mattina’s “Memory Bank” presents the danger that the devices we create to witness, measure and recall our experiences can become an end in themselves, to our peril.

To say that art is a cultural event is to wallow in redundancy, and different groups take different views of, for example, the ways our own bodies become sculptural objects of self-expression. Anyone who has seen the geometric fascinators worn by royalty at weddings or the magnificent floral displays worn by Black women in Church will understand why Inez Garcia felt it was important to find a way to bring the matter of heads as sculpture into the gallery. Using a couple of mirrors, to which she has attached feathers, faux fur, and silk florals arranged so that viewers can see themselves as if they were wearing the elaborate, exotic results, she asks the rhetorical question of whether we can ever succumb to the temptation to touch another person’s hair after it has touched us.

An overview of The Face of Utah Sculpture reveals the diversity of media and themes embraced by Utah artists in this open exhibition.

Jonna Ramey’s “Briney”

It seems appropriate to say that while fixating on the more experimental works comes easily, there are conventional pieces worth checking out. But the reality is that even these generally depart from expectations. Laura Lee Stay’s tabletop bronze figure, “Taking Flight,” turns Art Nouveau conventions into a parable about first liberating yourself, then extending that freedom to others. Perennial driftwood dreamer Michael Melik’s “Fairytale” redeems the Surreal eroticism of Salvador Dalí. In “Longhorn,” a reborn Western classic, Andrew Shaffer’s bronze cattle skull illuminates its layered glass spread of horns.

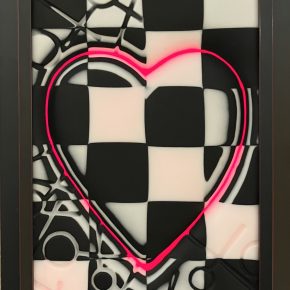

Speaking of glass, this material, once rare in these parts, now shows up in substantial quantities and high quality, but more importantly, a wide variety of techniques and concepts. In “Hugs and Kisses,” Dan Cummings continues to fuse opaque black and white glass that he then carves, but here he’s added interior lighting to bring the work to life. Kerry Transtrum’s “Fence Me In” features a blown vessel shaped with a couple of loops of barbed wire. And Stephen Teuscher’s “Percival, The War-Torn General” combines a realistic bas-relief lion in white paste with an expressionistic patina of brilliant yellow. Along with Shaffer’s bull and Teuscher’s lion, Suzanne Larson’s “Underwater” shares a diversely expressed theme of animals in nature.

- Dan Cummings, “Hugs and Kisses”

- Suzanne Larson’s “Underwater”

- Stephen Teuscher’s “Percival, the War-Torn General” paired with Kerry Transtrum’s “Fence Me In”

A final thought for here and now is how much the sculptor’s traditional life, work and workspace has changed in our time. From a dusty, cluttered, and exclusively masculine domain from the Renaissance to the early Modern age, it has become a place where women cast molten metal and carve rock with equal skill. Most mind-altering, perhaps, is Jason Lanegan’s family room, where he and his family sit in the evening, cutting up travel documents and maps of places far and near they’ve visited, then rolling the resulting scraps into thousands of colorful, tapered beads they hang, along with keys and toys and tools that are equally full of memories—talismans that trail from his domestic reliquaries like the tails of so many comets, or sparks from a campfire around which they might share their recollections. When they grow up, these no-longer youngsters will have not only the memories stored in these sculptures, but thoughts of times spent together building them. It’s a new model of sculpting, not of a commercial venture or an egotistical challenge, but of art as a part of the lived, family experience: part of its bones and sinews.

Now that’s a thought to conjure with.

Jason Lanegan’s “Warren of Lost Keys”

Face of Utah Sculpture XXI, Utah Cultural Celebration Center, West Valley City, through August 27.

All images courtesy of the author.

Geoff Wichert objects to the term critic. He would rather be thought of as a advocate on behalf of those he writes about.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts

“Wasatch Assemblage Ensemble” . . . too perfect! An elite crew tacking remote locales in search of the next sublime object.

And I love your observation of Lanegan at home, making paper beads with his family . . . the stories and memories abroad or across the state now come home . . . twisting and tangling literally into his works . . . this is important stuff.

Always a pleasure reading your work. Art as ritual is a powerful connection in my work and I love the metaphors you used as you discussed it. Thank you for your kind words.

Thank you, Geoff! It’s always a great joy to both hear and read your interpretations. I always leave with a greater appreciation of the works, often lost in the initial tangle of installing the exhibitions.